Hey everyone – it has been a while since I posted anything. In fact, the last time I posted was during the NecronomiCon back in August 2019. This year has been crazy with all of the Harmful Algal Blooms I have had to deal with over the summer and fall as part of my job as a Limnologist / Environmental Consultant. While the blooms are slooooowly dissipating, I have a little free time to start posting again on Lovecraftian Science. I will try to make these posts fairly routine (maybe twice a month) and to do that they may be brief. Also, working on finishing up Volume 3 of the Journal of Lovecraftian Science now that the summer is over. Again, I apologize to everyone who has contributed to the Kickstarter for the additional delays. Please be patient; I am hoping to ship them out before the end of this year.

I was fortunate enough to give two presentation at the NecronomiCon in August 2019. The first talk was on Lovecraftian Ecosystems so the next series of posts will be on this subject. This first post is a discussion on history of the term of ecosystem.

The formal definition of an ecosystem is “…a community of organisms and their physical environment interacting as an ecological unit” (Lincoln, et. al. 1988). The word “ecosystem” was first defined by British Ecologist Arthur Tansley in 1935 and was first used to describe the transfer of material between organisms and their environment. Again, in 1935 Tansley defined the ecosystem as:

…the whole system (in the sense of physics) including not only the organism-complex, but also the whole complex of physical factors forming what we call the environment of the biome – the habitat factors in the widest sense (from McIntosh, 1985).

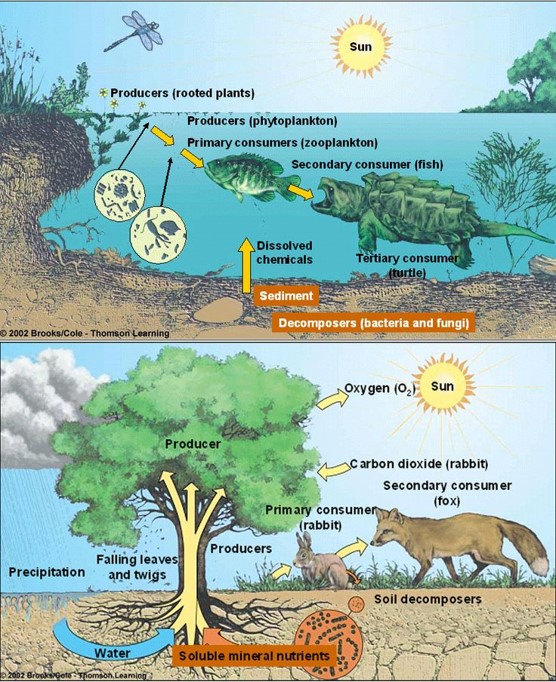

Examples of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems

Examples of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems

However, it was G. Evelyn Hutchinson who re-defined the concept of ecosystem to be more quantitative in nature. In fact, it was Hutchinson and his post-doctoral associate Raymond Lindeman who moved ecology from a descriptive “soft science” of the 18th / 19th to more of a quantitative “hard science” of the 20th century. Instead of merely identifying species and describing their life cycles and interactions, math and statistics could be used with models to construct experiments to predict how organisms interact and react in their environment and among themselves. Hutchinson and Lindeman were limnologists (the sub-discipline of ecology I study / practice) and so many of these ideas were first initiated in focusing on the biogeochemistry and the transfer of energy among trophic levels in lake ecosystems. In a sense, it was logical for ecosystem science to begin with lakes since they appear to be very clearly defined and bounded ecosystems (as will be discussed later this distinct boundary is not the case).

Photograph of a young G. Evelyn Hutchinson

Photograph of a young G. Evelyn Hutchinson

Prior to Lovecraft’s time, the “hard sciences” were thought of as astronomy, physics and chemistry, while biology and ecology were “softer “sciences that focused primarily on descriptions. This hierarchical view of the sciences was developed and promoted by the French philosopher and writer Isidore Marie Auguste Francois Xavier Comte (1798 – 1857). Comte stated that astronomy was the most general of the sciences, followed by (in hierarchical order) physics, chemistry, biology and sociology. I’m sure Lovecraft would have agreed with this hierarchy of the sciences, with astronomy being the hardest or “most pure.”

A hard science is typically described as one where controlled experiments can be constructed and performed to test hypotheses, with the use of math and statistics. In turn, the results of the experiments can be used to make testable predictions about the natural world. Over the last two hundred years we have seen the softer sciences utilize a more quantitative, scientific approach and this is particularly the case for biology, including the sub-discipline of ecology.

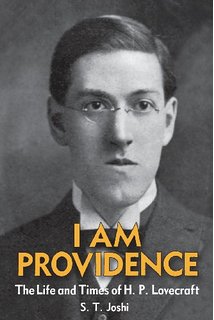

Ironically, it was the quantitative aspects of astronomy and chemistry that kept him from pursuing a career in either field. As Joshi has cited in, I Am Providence: The Life and Times of H.P. Lovecraft (Joshi, 2013), Lovecraft stated:

In studies I was not bad – except for mathematics, which repelled and exhausted me. I passed in these subjects – but just about that. Or rather, it was algebra which formed the bugbear. Geometry was not so bad. But the whole thing disappointed me bitterly, for I was then intending to pursue astronomy as a career, and of course advanced astronomy is simply a mass of mathematics. That was the first major set-back I ever received – the first time I was ever brought up short against a consciousness of my own limitations. It was clear to me that I hadn’t brains enough to be an astronomer – and that was a pill I couldn’t swallow with equanimity.

This is from a letter Lovecraft wrote to Robert E. Howard, dated 25-29 March 1933.

While the term “ecosystem” was first coined and used in the scientific literature in the early 20th century, it was not widely used in popular culture at the time. Thus, it is not surprising that I could not find the word in any of Lovecraft’s stories or other writings. However, while he did not use the word, many of his stories include several of the ideas and concepts associated with ecosystems and that is what we will review over the next set of blogs. Next time we will talk about the ecosystem-based alterations associated with his tale “The Colour Out of Space.” Thank you – Fred.